Montessori Life, Spring 2017

By Cameron Camp, Vince Antenucci, Alice Roberts, Tim Fickenscher, Jérôme Erkes, and Trudy Neal

More than 20 years ago, the concept of using the Montessori Method as a treatment for dementia was discussed in the pages of Montessori Life (Vance, Camp, Kabacoff, & Greenwalt, 1996). At that time, research was just beginning on this topic. Since that initial article, the use of the Montessori Method with older adults with dementia has taken root on an international scale. It seems timely to review the development and dissemination of this concept, and to discuss plans for its continued evolution.

In 1999, a manual describing activities based on the Montessori Method that could be used with persons with dementia was published (Camp). It has since been published in a variety of languages, including French, Spanish, Greek, Japanese, and Mandarin (e.g., Buiza, Etxeberria, Yangua, & Camp, 2007). Other manuals and publications have followed (e.g., Camp, 2006; 2010; 2013; Camp, Orsulic-Jeras, Lee, & Judge, 2004; Camp, Schneider, Orsulic-Jeras, Mattern, McGowan, Antenucci, Malone, & Gorzelle, 2006; Elliot, 2012; Giroux, Robichaud, & Paradis, 2010; Jarrott, Gozali, & Gigliotti, 2008; Joltin, Camp, Noble, & Antenucci, 2012; Lin, 2014; Lin, Yang, Kao, Wu, Tang, & Lin, 2009; Lin, Huang, Watson, Wu, & Lee, 2011; Love, 2006; Mahendra, Hopper, Bayles, Azuma, Cleary, & Kim, 2006; Malone & Camp, 2007; Skrajner, Malone, Camp, McGowan, & Gorzelle, 2007; Vance & Johns, 2003; Van der Ploeg, Eppingstall, Camp, Runci, Taffe, & O’Connor, 2013). A video created in the U.S. describing the use of Montessori-based activities when visiting persons with dementia has been translated into French, German, Italian, Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish (see Appendix, page 47, for more information on this and other videos).

Today, active programs in the use of the Montessori Method as adapted for persons with dementia can be found in France, Australia, Singapore, Spain, Ireland, Canada, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Switzerland, and the United States. Plans are underway to expand this approach to Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, the Czech Republic, China, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and to take it “home” to Italy. These programs take place in adult day health centers, assisted living residences, skilled nursing residences, and in-home settings. The unifying factor in all of these programs is a set of core values central to the Montessori philosophy—respect, dignity, and equality. Montessori treated children as persons; by the same token, we must see the person in a person with dementia. And just as Montessori revolutionized education for children by providing choice within prepared environments, the same way of thinking can revolutionize the way we work with persons with dementia.

By creating materials and environments that allowed accomplishment and a sense of purpose, Montessori emphasized what a child was capable of doing. She instilled both independence and the ability to work collaboratively in her students. An ultimate goal was to enable the child to become a member of a community and society who could contribute in positive and meaningful ways. Similarly, the Montessori Method applied to dementia emphasizes the use of remaining capabilities, the ability to improve with practice, and the need to enable a person who happens to have dementia to be as independent as possible, to engage in purposeful and meaningful activity, and to have social roles within a community connected with the larger world.

For persons with dementia, training involves emphasis on the previously mentioned values of respect, dignity, and equality. Caregivers are trained to demonstrate these values in all interactions with residents, e.g., always address the person with dementia face-to-face and at their eye level, rather than literally talking down to a person in a wheelchair. Providing choice in every interaction with the person with dementia is a key feature of this approach, such as holding up two shirts and asking, “Would you like to wear this shirt or this shirt?”

Having the opportunity to see dishes on a menu enables persons with dementia to make informed choices during meals. Choice then expands to residents helping with food preparation for meals, creating committees to determine menus, outings, selection of entertainment, creation of rituals for greeting new community members, decisions about how to peacefully deal with conflicts, etc. Activities focus on principles such as demonstrating how to perform an activity before asking a person with dementia to do it (using clear, slow demonstrations as well as the application of the three-period lesson), breaking down activities into steps that can be performed one at a time, extensive use of external aids and templates, etc. In addition, persons with earlier-stage dementia learn to lead groups of persons with more advanced dementia in activities. Training for caregivers is provided by those who have extensive experience working with individuals with dementia, and who have themselves received training from master trainers with expertise in the Montessori Method as applied to persons with dementia.

EXAMPLES IN DAY CENTERS

The Montessori Method was applied over the course of a year in an adult day health center in Queensland, Australia, where clients with dementia came to take part in activities during weekdays and then returned home with family members for evenings and weekends. At the end of the year, clients with dementia were able to come to the center, set up and conduct their own activities, and essentially run the program. Just as the Casa dei Bambini was the children’s house, so, in this case, the program became the clients’ program. In fact, clients planned and successfully executed a surprise birthday celebration for the center’s manager. One client with advanced dementia spent a long time rolling a crepe streamer along the bar of a stairway as his contribution to the event. He used the capacities he had available and was able to be part of his community’s celebration.

In 2015, Alzheimer’s Australia Vic (an organization to support families of and persons with dementia in Victoria State, Australia) completed a pilot project to evaluate the impact of the Montessori Method on the engagement of clients with dementia, in Melbourne. As part of the project, staff participated in Montessori workshops and on-site coaching. Over time, the shift in staff focus to the abilities and interests of each client resulted in some heartwarming experiences. One client, who previously spent much of the day napping, was encouraged to rekindle his interest in cooking and happily engaged in making biscuits and pizza. Staff members were also surprised to discover many clients could read and enjoyed participating in and even leading small reading and discussion groups. Instead of being passive recipients of care from staff, clients became actively involved. Researchers from the Australian Centre for Evidence-Based Aged Care, La Trobe University, evaluated the project, and, despite the small sample size and other study limitations, found statistically significant increases in clients’ active engagement, pleasure, and helping others, along with decreases in nonengagement. One client commented, “I like helping out. It gives me something to do, and I feel like I’m doing something worthwhile.” A positive response in staff attitudes to dementia was also noted—there was an increase in activity, general noise level, and enthusiasm of both staff and clients during activities.

In an adult day program in Paris, a female client had the habit of disrupting the morning reading of the day’s activity schedule. This led to other clients telling her to be quiet, and tensions rose. After some Montessori training, staff members changed their approach. They asked the woman to read the activity schedule for the group. She did so in a very dignified manner, and when another client began to interrupt with a question, the woman responded, “You will have to wait until I am finished, please.”

In a Singapore Montessori-based day center for adults with dementia, a client who had been a nurse selected items for the center’s first-aid kit, while another client who had been an engineer put the contents into the kit so that they could be seen and used efficiently. As a team, they were able to make this important contribution to the center.

In a day-care center linked to a nursing home in Lausanne, Switzerland, one year after beginning implementation of the Montessori Method, clients with dementia were able to run the daily lunch program. They set tables for meals, installed a buffet, took food by themselves and helped those who were not able to do so, cleared the tables, and did the dishes. Intervention from staff was not needed.

In another day-care center, in Avignon, France, clients with dementia created a project to collect money to help abandoned animals. They crafted many different items (nesting boxes, gift cards, jams, etc.), sold them, and donated the proceeds to an animal rescue center.

EXAMPLES in ASSISTED LIVING RESIDENCES

At an assisted living residence in Beachwood, OH, there is a unit called Helen’s Place for persons with memory impairment. Residents choose their outing destinations, what will be grown in their garden, and have developed their own rules for visitors (such as, “Don’t put your feet on the furniture,” and “Please don’t come to view this place during meals because no one wants to be watched while eating”).

In an Oregon assisted living facility, residents with dementia began a beer-making club. Each month they start a new beer, transfer another beer from primary to secondary storage, and bottle a third. They have won prizes for their creations and even set up a bistro so that they can share their creations with visitors. Now a local home-brewing club meets regularly at the assisted living residence, with club members and residents with dementia working together to create new brews. One of these recipes was produced by a local microbrewery, and kegs were sold to raise funds for the Alzheimer’s Association.

In an assisted living residence in Arizona, residents with dementia go to used furniture stores, acquire old wooden pieces, and refurbish them. The beautiful “new” furniture is sold, and funds collected are used to support the local Alzheimer’s Association walk. Thus far, more than $10,000 has been raised.

In a dementia unit in Avignon, France, environmental adaptations (i.e., the creation of a prepared environment) led to huge strides in the independence of residents, who progressively learned to use the environment by themselves. They became able to find their rooms, locate activity materials, find tools needed to take care of the environment (such as brooms or dishcloths), and independently set and clear tables.

EXAMPLES IN NURSING HOMES

In a nursing home for persons with moderate to advanced dementia, in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, residents have a memorial section in their garden. When a resident dies, a rock is placed in the garden with the name of the resident and the dates of birth and death. Family members, residents, and staff members come to a ceremony for placing the stone and honoring the deceased. When this was relayed to a director of a nursing home in France, he asked, “Would not that make residents cry?” The first author of this article answered, “Of course. People cry at funerals. This is so much better than not having a ceremony and people wondering what has become of a deceased resident who suddenly is ‘missing.’”

In a different nursing home in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, when health inspectors came to visit, residents with moderate to severe dementia welcomed the inspectors and led them on a tour, answering their questions, resulting in the nursing home’s highest score on an inspection to date. In fact, after the visit, the inspectors asked to check medical records, as the residents did not seemed to have dementia. Subsequently, the nursing home received a prize from a Swiss foundation for the quality of its care.

In a nursing home in the south of France, residents with dementia prepare food to serve to members of their village on Sundays. They go to the market to shop for the food, bring it back to the home to prepare it, and share the meal they make with their friends and neighbors. In the day-care center in Avignon mentioned earlier, residents created a play based on stories from their lives; vignettes portrayed what it was like to attend school, to live in German-occupied France, to experience liberation after the war, and so on. Family, friends, other residents, and staff members were invited to the show, and afterward there was a celebration with wine and song, in the courtyard, that stretched far into the evening.

In a nursing home in Victoria, Australia, residents prepare the environment for meals, have daily social roles, and live in an environment where independence and choice have become the culture of the community (Roberts, Morley, Walters, Malta, & Doyle, 2015). The same can be seen in some nursing homes in France. In another Australian nursing home, residents organized a walking club, tracking their daily distances in a “Walk around Australia.” They decided on a route on a map and measure their distance walked at the residence in terms of their distance on their route. When they “approach” cities, they write to the mayor and town council, telling of their trek, and often receive correspondence back from those cities’ officials.

In a nursing home in Spain, most residents with advanced dementia had historically been physically restrained. After adopting the Montessori Method, these residents would leave the center each morning to shop for food and then prepare it for their afternoon meal. Use of restraints dropped 94% over the course of 8 weeks, after starting the program.

As described earlier, in a nursing home in Lausanne, Switzerland, residents are now engaged in meaningful daily activities, with each resident playing a role based on individual capacities and choices. Residents also take part in larger projects: They organize the annual family party or make items, such as cards, jam, cookies, scarves, and even limoncello, to sell at a holiday market. The proceeds go toward outings for the residents (they decide the locations, of course).

The use of psychotropic medication has been reduced by 66% in the 2 years the Montessori program has been in existence. In addition, while there were seven psychiatric hospitalizations in 6 months before the program began, in the past 2 years, there has been just one.

EXAMPLES OF PEERS PRESENTING ACTIVITIES

In a Montessori classroom, older students are seen presenting lessons to younger students. In a similar way, older adults with early to moderate-stage dementia have been trained to serve as leaders of activities for groups of other persons with dementia (Skrajner & Camp, 2007; Skrajner, Haberman, Camp, Tusick, Frentiu, & Gorzelle, 2014). In one study, a woman with Huntington’s disease (a genetically based dementia that initially impairs motor function and typically occurs at a younger age than the onset of most cases of Alzheimer’s) was trained to lead a reading and discussion group for persons with Alzheimer’s disease (Mattern & Kane, 2007). She used a touch-screen computer connected to a large-screen display. Each page of the story was on a single frame of a slide presentation on the computer. The woman would ask a group member to read a page aloud for the rest of the group, and she could turn to the next page by touching the screen with her hand. She also would lead discussions of each story’s content. This example illustrates key elements of the Montessori Method, including emphasizing abilities of the individual, preparing an environment to enable successful task completion, and providing meaningful social roles within a community.

In the Lausanne, Switzerland, day-care center described earlier, clients are involved in running and leading activities (such as reading and discussion groups, adapted dice games, memory bingo, etc.) for the residents in the associated nursing home. These opportunities to help others allow the clients to enhance their self-esteem, have meaningful goals, and create social relationships in their community.

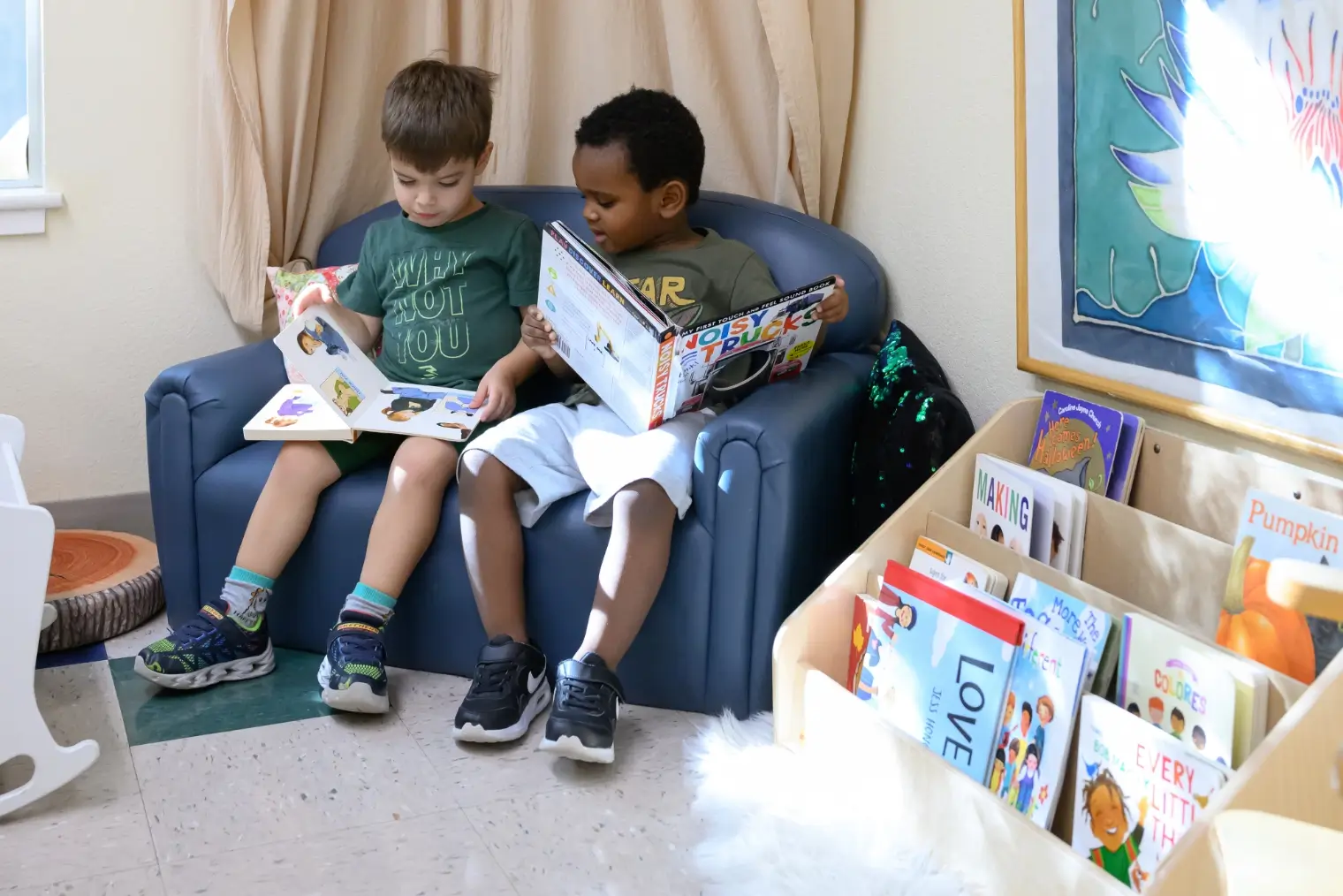

EXAMPLES OF INTERGENERATIONAL PROGRAMS

Intergenerational programming between children and persons with dementia has been successfully implemented by enabling older adults with memory impairment to present lessons in everyday living (such as how to fold clothes, set a table, use tools, etc.), as well as other activities, such as presentations of Sandpaper Letters, Knobbed Cylinders, and Spindle Rods (Camp & Lee, 2011; Lee, Camp, & Malone, 2007). Persons with dementia get better with practice and fully understand the importance of being able to teach children. Children, in turn, get an opportunity to interact with these older adults and come to form friendships with their “adopted grandparents.”

An interesting example of this approach is a program created by Montessori International School of the Plains (MISP), a nonprofit junior/senior high school in Omaha, NE (now named The Roberts Academy). An important and distinctive part of the school’s approach is its intergenerational program, designed with the help of Dr. Anna Fisher of Hillcrest Health Services (an organization providing senior living, memory care, and adult day services in Omaha). Montessori believed that learning continued throughout life. Additionally, research has demonstrated that the involvement of caring adults increases the likelihood that students will finish high school. And older adults often have the time and interest to provide the attention, encouragement, and interest in learning that moves young adults in a positive life direction.

The intergenerational program is held on Fridays, at an assisted living facility. Residents join Montessori students to participate in learning activities based on their interest and ability level. Residents who are in memory support and those who are minimally affected by dementia take part. Since the program’s inception, students have been able to participate in research studies involving the creation of materials and activities to be used by persons with dementia, along with the assessment of their effects. Additionally, they have been given the opportunity to gain some experience in health care and to take the lead in helping to solve major problems affecting society today.

Both students and residents enjoy the program and are having fun learning. Residents provide experience and history that cannot be learned from textbooks, and students gain life skills that can be applied in both an academic setting and in the workforce as they learn to be leaders, team members, community activists, and compassionate young adults. The intergenerational school truly is a place of lifelong learning.

Another example of Montessori intergenerational programming comes from a nursing home in Petit-Chezard, Switzerland. Residents regularly invite children from the local school to present activities about specific topics. For example, for Easter, they invited twenty-five 5and 6-year-old children to discuss eggs and chicks. Five residents with dementia worked with five children at work stations, presenting them activities such as a timeline puzzle about the growth of the chick inside the egg, egg painting, reading and discussion groups about hatching, a black room to look inside the egg with a lamp, and creation of Easter decorations. Each activity was adapted to the capacities of the residents and was fully led by them. Later, residents crafted Montessori activity materials for the children, such as dressing frames or the Pink Tower. Then they went to the school to offer their creations to the children, along with demonstrations on how to use them. Recently, the children asked to invite their older friends to the school to present their own activities to the adults with dementia.

EXAMPLES IN HOSPITAL SETTINGS

In a hospital in Northern Ireland, staff encouraged persons with dementia to write personal invitations to family members and friends for a tea being held at the hospital. As a result, attendance at this tea was significantly larger than had been seen in the past. In a hospital in Montpelier, France, persons with dementia on a special unit correspond with those who have been discharged from the unit, maintaining their sense of belonging to a special community.

In Toronto, Canada, a hospital’s emergency room has been using Montessori-based activities with persons with dementia. By focusing on engaging activity while in the emergency room, persons with dementia do not show the same levels of agitation, anxiety, and disorientation that are commonly seen in this setting.

In Lille, France, a special hospital unit dedicated to working with challenging individuals with dementia has adopted the Montessori Method. As a result, this hospital unit has been able to normalize these individuals and return them to their communities. The amount of time patients spend in this unit is half the time spent in similar units in French hospitals not using the Montessori Method.

While the utilization of the Montessori Method in medical settings might seem surprising, Maria Montessori proposed the creation of a “White Cross” organization during World War I, with the purpose of treating children of war. The plan was to create a cadre of “teacher-nurses” who would be trained not only in the Montessori Method as applied to traumatized children but also in first aid (Montessori, 1917). Four to six-person teams were to be trained in the United States and sent to France, Belgium, Serbia, Russia, and other places where refugees were gathered. Teams would consist of a head secretary, teachers, and outside workers (Montessori, 1917). Montessori insisted that there was no need to wait until the end of the war to begin the work. She saw the need and wanted to move forward immediately. We feel the same urgency and now are exploring the idea of creating a new level of training for Montessori teachers to enable them to work effectively with persons with dementia in a variety of settings. As always, we take our inspiration from Maria Montessori, who blazed the trail for us.

CONCLUSION

It is our hope that this description of the Montessori Method applied to persons with dementia has served to further illustrate the universality and international scope of Maria Montessori’s philosophy and values. Even a cursory reading of her works finds that her goal was to transform society. At the end of a presentation, in France, given by the first author of this article, on this approach to dementia care, a graduate student commented, “Now, I understand. This is not just about transforming care for persons with dementia. This is about changing civilization.” Respect, dignity, and equality are values that can indeed create civilizing attitudes and behaviors on a society-wide scale. When disenfranchised groups are recognized, given a voice, and included in the larger community, our society and world benefit. When we follow in Montessori’s footsteps, we lead the world to a better future.

About the Authors

CAMERON CAMP, PHD, is founder and director of research of the Center for Applied Research in Dementia, in Solon, OH, and a psychologist conducting research on the Montessori Method and dementia. A member of AMS, he taught child development at the New Orleans Montessori Training and Education Center. He now trains internationally in the use of the Montessori Method as treatment for dementia.

VINCE ANTENUCCI, MA, is training and research manager at the Center for Applied Research in Dementia.

ALICE ROBERTS, MA, is a teacher and administrator at The Roberts Academy, in Omaha, NE. She is AMS-credentialed (Elementary I–II, Secondary I–II) and AMI-credentialed (Early Childhood).

TIM FICKENSCHER, MED, is a teacher and administrator at The Roberts Academy, in Omaha, NE. He is AMS-credentialed (Secondary I–II).

JÉRÔME ERKES, MSC, is director of research and development for AG&D, headquartered in Paris, France, which trains and promotes the use of the Montessori Method applied to persons with dementia.

TRUDY NEAL, MSC (DEMENTIA CARE), is a dementia educator and consultant for Alzheimer’s Australia Vic.

References

Buiza, C., Etxeberria, I., Yangua, J., & Camp, C. (2007). Actividades basadas en el método Montessori para personas con demencia: Volumen I. Laboratorios Andrómaco, SA.

Camp, C. J. (Ed.). (1999). Montessori-based activities for persons with dementia: Volume 1. Beachwood, OH: Menorah Park Center for Senior Living.

Camp, C. J. (2006). Montessori-Based Dementia Programming™ in long-term care: A case study of disseminating an intervention for persons with dementia. In R. C. Intrieri & L. Hyer (Eds.), Clinical applied gerontological interventions in long-term care (295–314). New York: Springer.

Camp, C. J. (2010). Origins of Montessori programming for dementia. Non-Pharmacological Therapies in Dementia, 1(2), 163–174.

Camp, C. J. (2013). The Montessori approach to dementia care. Australian Journal of Dementia Care, 2(5), 10–11.

Camp, C. J., & Lee, M. M. (2011). Montessori-based activities as a trans-generational interface for persons with dementia and preschool children. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 9, 366–373.

Camp, C. J., Orsulic-Jeras, S., Lee, M. M., & Judge, K. S. (2004). Effects of a Montessori-based intergenerational program on engagement and affect for adult day care clients with dementia. In M. L. Wykle, P. J. Whitehouse, & D. L. Morris (Eds.), Successful aging through the life span: Intergenerational issues in health. (159–176) New York: Springer.

Camp, C. J., Schneider, N., Orsulic-Jeras, S., Mattern, J., McGowan, A., Antenucci, V. M., Malone, M. L., & Gorzelle, G. J. (2006). Montessori-based activities for persons with dementia: Volume 2. Beachwood, OH: Menorah Park Center for Senior Living.

Elliot, G. (2012). Montessori methods for dementia: Focusing on the person and the prepared environment (U.S. Edition). Solon, OH: Center for Applied Research in Dementia.

Giroux, D., Robichaud, L., & Paradis, M. (2010). Using the Montessori approach for a clientele with cognitive impairments: A quasi-experimental study design. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 71(1), 23–41.

Jarrott, S. E., Gozali, T., & Gigliotti, C. M. (2008). Montessori programming for persons with dementia in the group setting: An analysis of engagement and affect. Dementia, 7(1), 109–125.

Joltin, A., Camp, C. J., Noble, B. H., & Antenucci, V. M. (2012). A different visit: Activities for caregivers and their loved ones with memory impairment (2nd ed.). Solon, OH: Center for Applied Research in Dementia.

Lee, M. M., Camp, C. J., & Malone, M. L. (2007). Effects of intergenerational Montessori-based activities programming on engagement of nursing home residents with dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2(3), 1–7.

Lin, L. C. (2014). Efficacy of spaced retrieval only compared to a combination of spaced retrieval with Montessori-based activities in improving overeating of residents with dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 10(4), 739.

Lin, L. C., Huang, Y. J., Watson, R., Wu, S. C., & Lee, Y. C. (2011). Using a Montessori method to increase eating ability for institutionalized residents with dementia: A crossover design. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(21–22), 3092–3101.

Lin, L. C., Yang, M., Kao, C., Wu, S., Tang, S., and Lin, J. (2009). Using acupressure and Montessori-based activities to decrease agitation in residents with dementia: A crossover trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1022–1029.

Love, K. (2006). Montessori-based activities: A guide for using therapeutic engagement to enhance function for individuals with dementia. District of Columbia Office on Aging, Washington DC.

Mahendra, N., Hopper, T., Bayles, K. A., Azuma, T., Cleary, S., & Kim, E. (2006). Evidence-based practice recommendations for working with individuals with dementia: Montessori-based interventions. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 14(1), XV–XXV.

Malone, M. L., & Camp, C. J. (2007). Montessori-Based Dementia Programming®: Providing tools for engagement. Dementia, 6, 150–157.

Mattern, J. M., & Kane, E. (2007). Huntington’s disease client as activity leader. Clinical Gerontologist, 30(4), 93–100.

Montessori, M. (1917). The White Cross, pamphlet held at AMI, Doc. 5909. Maria Montessori Archives (Amsterdam: Association Montessori Internationale).

Roberts, G., Morley, C., Walters, W., Malta, S., & Doyle, C. (2015). Caring for people with dementia in residential aged care: Successes with a composite person-centered care model featuring Montessori-based activities. Geriatric Nursing, 36(2), 106–110.

Skrajner, M. J., & Camp, C. J. (2007). Resident-assisted Montessori programming (RAMP™): Use of a small group reading activity run by persons with dementia in adult day health care and long-term care settings. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 22(1), 27–36.

Skrajner, M. J., Haberman, J. L., Camp, C. J., Tusick, M., Frentiu, C., & Gorzelle, G. (2014). Effects of using nursing home residents to serve as group activity leaders: Lessons learned from the RAP Project. Dementia, 13(2), 274–285.

Skrajner, M. J., Malone, M. L., Camp, C. J., McGowan, A., & Gorzelle, G. J. (2007). Research in practice I: Montessori-Based Dementia Programming® (MBDP). Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 8(1), 53–64.

Vance, D., Camp, C. J., Kabacoff, M., & Greenwalt, L. (1996). Montessori methods: Innovative interventions for adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Montessori Life, 8, 10–12. Vance, D. E., & Johns, R. N. (2003). Montessori improved cognitive domains in adults with

Alzheimer’s disease. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 20(3–4), 19–33.

Van der Ploeg, E. S., Eppingstall, B., Camp, C. J., Runci, S. J., Taffe, J., & O’Connor, D. W. (2013). A randomized crossover trial to study the effect of personalized, one-to-one interaction using Montessori-based activities on agitation, affect and engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 25, 565–575.

Appendix: Video References

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLDwzgRTbVA

A Different Visit: Montessori-Based Activities for People with Alzheimer’s/Dementia

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Y6LCpL8HUU

Purposeful Activities for Dementia: Alzheimer’s Australia Vic

www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_8puCns9E0

Dr. Cameron Camp: Relate, Motivate, Appreciate—A Montessori Resource

www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkJc2Rk6IgA

Montessori: An Aid for Rehabilitation in Dementia

www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkJc2Rk6IgA

The Montessori Principles

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1LCRrcxlrXE

Wattle’s Innovative Program for People Living with Dementia—Australia

A number of other videos are available at www.cen4ard.com and at the French website www.ag-d.fr/actualites/en-video.