Decolonizing Montessori: An Antiracist Approach to Our Practice (From the Winter 2021 issue of Montessori Life magazine)

This article was featured in our 2021 Winter edition of Montessori Life magazine. Read the full issue online (AMS members only).

AMS members also receive a print subscription to Montessori Life magazine. Become a member today to receive your own subscription plus access to the complete digital archives.

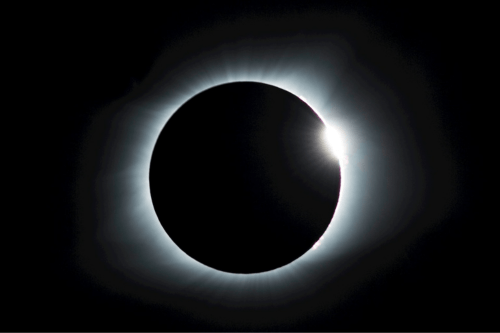

In Montessori, we teach big history, dating back billions of years to the beginning of the universe. We trace big history, in the hopes of instilling in children the great mystery of existence and how this moment is but a blink of an eye on the Timeline of Life. Similarly, when we teach U.S. history, it is with the understanding that this country’s existence makes up mere seconds on that timeline. And when we talk about systemic oppression, it is with the understanding that it is a part of our infant country’s identity, the very bedrock from which it was built, on land we viciously stole from Native Americans.

In the United States, legal slavery no longer exists. But on the Timeline of Life, including the period we are living in, the effects of slavery are very much present. They exist in the prison industrial complex, in voter suppression dating back to Jim Crow laws, in the segregation of schools shrouded in “school choice,” and in the school-to-prison pipeline (Schlosser, 1998; Tatum, 2017); ACLU). They exist in redlining that, in the 20th century, systematically blocked Black families from class mobility, a practice which continues today in subtler, less overt ways (Tatum, 2017). They exist in the uncanny mortality numbers for Black and Indigenous birthing mothers (CDC, 2019). They exist in the countless murders of Black men and women at the hands of law enforcement (Tatum, 2017). They exist in the disproportionate number of people of color who are “essential workers” dying from COVID-19 (CDC, 2020). We often view education as a pathway out of these realities, but we can’t deny it is very much a part of the power structure designed to elevate and affirm white lives.

All of this is, by design, to uphold white supremacy. As a white woman, and a Montessori teacher, who continues to reap the advantages of stolen Native American land and a capitalist system built to serve me, I must find ways to integrate the truth of this history and present into my practice, into my self-work, and into my classroom. But how do we begin the journey of decolonizing—replacing solely Western interpretations of history with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) perspectives, and restoring BIPOC culture and traditional ways—when our entire educational system was built to support, affirm, and uphold white supremacy (Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc., 2017)? At the start of every journey is an awareness of the truth.

Ashley Causey-Golden, owner of Afrocentric Montessori, a company that sells handmade materials and curriculum for Black children, says that before we can begin this work, we have to recognize the history of education in the United States:

When we talk about decolonization, we have to acknowledge the origins of the education system within the United States. Education has been a tool that has been weaponized to limit access to non-white children and families, strip the language and cultural identity from Indigenous children, and, through the use of textbooks and learning materials, provide teachers and students with a Eurocentric view of world history. These actions led to our consumption of colonized Western ideals, which equated to the erasure of the historical truths of Black, Indigenous, and non-Western cultures. (personal communication, 7/15/20)

For Koren Clark, the anti-Blackness of education is by design. She is co-owner of KnowThySelf Inc., which offers culturally relevant Montessori materials, and director of teacher engagement at Wildflower Schools, a network of Montessori microschools across the country.

The decision to make education illegal for an African American person comes from a deep-seated fear that self-empowerment will topple the inequitable colonial political and economic structure that America was built on. Conversely, the ways in which the American educational system has operated as a system of cultural deprivation and dominant white cultural assimilation is further problematic, and a key structural component of colonialism. (personal communications, 7/10/20, 10/19/20)

Once we identify the problem, it is time to search for solutions. It is important to remember that solutions to these problems are not onetime fixes but require a lifetime of work and effort. We can examine solutions within the framework of Montessori philosophy: the prepared adult, the prepared environment, and the liberated child.

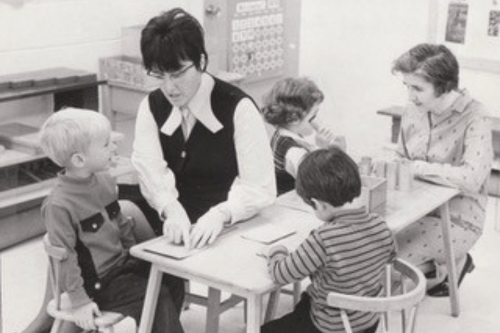

The Prepared Adult

In Montessori practice, we spend a lot of time talking about “the prepared adult.” Much of this focuses on self-work, removed from the lens of antiracist work. However, in order to be prepared adults in a decolonized classroom, we must confront our own racist ideologies and practices. Author Ibram X. Kendi (2019) proposes that if you are not actively engaging in antiracist activities then you are likely engaged in racist activities; there is no neutrality. This is often the mistake that well-intentioned white people make.

I have been an activist for as long as I can remember. I minored in women’s studies and I am queer. I have long had language for systematic oppression, but I completely skipped over the self-examination piece. I became a teacher after decades of weary work as a journalist and activist, in which I never saw the results I’d hoped for. I thought, maybe if I can have a part in the early formation of a child, I might be able to make a greater impact. Many well-intentioned white teachers enter the field with this same naive understanding; like me, they don’t take the time to examine the ways they enforce white supremacy every day. When I entered the classroom, I had a strong theoretical framework for both antiracism and education, but I still believed I was apart from this system, that I was not a racist. And it wasn’t until I could say, “I am a racist,” that the real work of decolonizing my classroom could begin. This process started when my mentor helped me see how my internal biases were playing out in my classroom—and the process continues today.

“When teachers are able to recognize and remove the walls or barriers that surround their worldview, they can better see the children’s needs and their light within,” Clark explains. “There is also an opportunity for the teacher to see clearly the cultural, emotional, personal identity, and needs of the child through a purified lens, and finally have a chance to serve the child’s needs and strengthen their identity.”

The self-work of a guide is spiritual. As Montessori (1967, p. 8) wrote,

Now let us imagine an ardent mystic soul that observes all the revelations of a little child’s mind so that with mingled feelings of respect, love, holy curiosity, and longing for the very heights of heaven, he may learn the way of his own proper perfection and thus be able to bring it fairly into the midst of a classroom filled with little children.

What this beautiful piece of prose suggests is that the role of a teacher, or guide, as Montessori called us, is nothing short of revolutionary. While deeply spiritual, it is also committed to unlocking higher-level thinking, promoting freedom and independence, and suggesting that children hold truths inside them that adults, unfortunately, have unlearned as we age.

In The Discovery of the Child (1967), Montessori proposes that the teacher is a scientist, and the ultimate aim of education is liberation. When we approach the child with our personal biases in check, allow for expansive thinking and creation with the help of the prepared environment, we can facilitate children’s journey of finding their cosmic task and the ideas and subjects that uniquely inspire them.

The Prepared Environment

The prepared environment is more than the materials on the shelf: It is also the curriculum, the child, and the community.

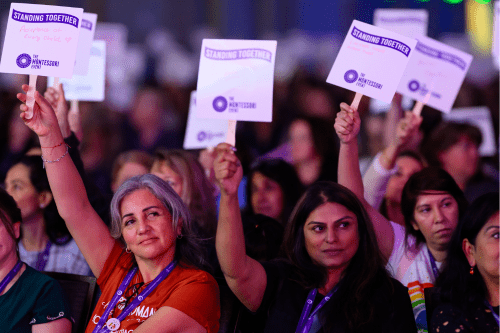

One of the main ideas that Clark conveys when she offers workshops at Montessori conferences across the country is that instead of being married to the Montessori Method, we must be married to the philosophy. This requires evolution in practice and constant self-reflection.

I work at Academia Ana Marie Sandoval, in Northwest Denver. Once a culturally rich Latinx community, the neighborhood has heavily gentrified in the last 10 years. The school is dual-language and Montessori, a model that was conceived to support the many bilingual students in the community. However, now that the neighborhood has become predominantly white and the dominant language English, Sandoval recruits students from all over the city to support our mission. What was once a neighborhood school for Latinx students now requires a long commute for some families wishing to have what we offer. It is impossible to not see these dynamics also at play in the classroom.

I take walks with my Upper Elementary students in the neighborhood. We notice shuttered businesses and painted-over murals, remaining tributes to a community barely visible. Our walk is front-ended with literary analysis of the work of local poet and activist Bobby LeFebre. We then walk to La Raza Park (“People’s Park”), the only name many locals use for this space, though its official name is Columbus Park. (A renaming/reclaiming process is currently underway.) This park, bearing the name of one of our country’s first and most violent colonizers, is home to one of Denver’s most beautiful Chicano history murals. It is easy for the kids to see the irony.

When we return to school, my students reflect on what makes a neighborhood. This serves as a launchpad for us to explore cultural pride, white privilege, appropriation, and many more topics that the children are so very present and available for.

Both Clark and Causey-Golden make materials to reflect back to Black children who they are, and instill a positive self-image. One of KnowThySelf’s materials, a 3-part card set designed to help the child understand advantages of the various phenotypes associated with racial diversity, would be a great addition to the Third Great Lesson, The Coming of Humans. Afrocentric Montessori’s offerings align more with the Primary level and include materials like a lacing set featuring the Black Nationalist flag, a djembe drum, an ankh aan Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol), and the continent of Africa.

Clark says,

It was painful for me to witness children move on from elementary school without an understanding of the unique assets that make up their own identity. Many children today are esteem-illiterate and struggle to excel and express themselves in their fullest. Unfortunately, esteem is a casualty of racism, and it hits children of color the hardest. Our materials allow children to understand race as a social construct and allow children to see clearly the environmental advantages of our diverse human phenotypes.

For Causey-Golden, having materials that empower Black children goes beyond the books on the shelf.

It was important to me to make sure the materials I created went beyond the narratives of hardships, poverty, resilience, and success stories because our narratives are much deeper. I wanted to make sure that I included joy, community, and grounding practices that connect to the Earth and our ancestors. These are the aspects that need to be included and embraced within the curriculum used in classrooms.

For white educators, it is important that we build positive relationships with our BIPOC children and invite them (and their families) to bring their traditions and history into our classrooms. We also need to teach white children about our country’s dark history. We can do this while also celebrating their cultural identities.

The Liberated Child

The aim of all this work, of course, is to help in the formation of the “liberated child.” Maria Montessori wrote of the liberatory nature of this pedagogy in many places: “The concept of liberty which should inspire teaching is, on the other hand, universal: it is the liberation of a life repressed by an infinite number of obstacles which oppose harmonious development, both physical and spiritual” (1967, p. 11).

Clark agrees that this goal should guide our practice.

Montessori children are empowered every day to solve problems autonomously in the classroom. When Montessori teachers embed critical consciousness strength building in each classroom, Montessori students can learn to effectively solve big problems in society, and gain the decolonial lens necessary to give them what they need for their ultimate freedom and full expression of their humanity.

I was once giving a lesson to a group of students about the true nature of Europeans’ arrival to the Americas. It was a somber and honest lesson that forced my students to confront many of their previously held ideas. One of my Latinx students asked, “Are you saying we are bad?” Before I could answer the question, I wanted to uncover who the “we” was, so I asked her. She replied, “white people.” I instinctively said, “Well, you are not white.” This answer showed my ignorance about the intersection of race and ethnicity. I assumed that this child would not identify as white because of her Latinx background. But many races within the Latinx community have been impacted by colonialism, and this child identified as white. I ultimately answered the question by stating that no, white people are not inherently bad, but white supremacy is. Later, I would follow up with the student to do more processing about her cultural understanding of the world and her family’s place in it. It is a conversation that has never left me, and to this day is one I feel ill-equipped for, but I am willing to face the discomfort of my own biases and misunderstandings to dive into other similar conversations.

Ultimately, as Montessorians, we believe the child is the key. We are merely guides on their journey. If we truly believe this, then we must work to remove whatever biases get in our own way of helping children unlock their liberated self.

The Cosmic curriculum is the thread holding the entire Montessori pedagogy together, anchoring the child’s education to the existential questions of “Who am I?” “Where did I come from?” And “Why am I here?”

The journey to answer these questions is a lifelong one that we aim to inspire in the child. But how does one truly, intrinsically inspire this? Cosmic Education connects children to their past, present, and future and provides a cultural context to their very existence. We trace our ancestry back to one continent and one time. The awe and reverence formed from this deep understanding create the framework of Peace education, where each child is invited to see themselves as “co-creator” of the universe and come to the “realization that life, and all its diverse forms, human and non-human, is indivisibly one” (Duffy & Duffy, 2002, p. 4).

But, in order to embrace this oneness, we must acknowledge not only the beauty of our differences but how they have been used to separate us.

Clark explains,

When we think about the birth of humanity, we cannot help but to think of the medium through which all people are birthed and developed—culture. Nothing is void of culture. Therefore we must teach children to recognize and respect their own culture and that of those around them. Due to the fact that we live in a society that is dominated by one European cultural norm, we must also teach children how to develop their own critical consciousness muscles. That is the key to decolonization in education.

Lifelong Action

Until Montessorians do the self-work to look at their internal biases and confront how they play out in the classroom, much of this will still feel theoretical. Maia Blankenship, a Montessori parent, Wildflower entrepreneur, and former Montessori child, calls the work lifelong. “You can’t have a liberated child without a liberated adult,” she says. “My journey in antiracism never ends. It is a commitment I make and action I take. Being antiracist is a verb” (personal communication, 7/16/20).

There are many things teachers, schools, and the larger Montessori community can do right now to address racism and decolonize our work. Here are five:

- Attend an anti-bias training and read the leading books on antiracist work in the classroom.

- Create an antiracist mission for your school.

- Involve parents and families in antiracist work.

- Amplify the voices of Montessori teachers of the global majority.

- Contact your local and national Montessori organizations and teacher training centers and urge them to include ABAR (anti-bias, antiracist) training as part of their programs.

“To white Montessorians: let’s not just make all these [antiracist] books sell out, but let’s center BIPOC voices. Let’s involve ourselves in the cultural experiences of others,” Blankenship continues. “Trust Black women, and listen to BIPOC leaders. There is no playbook and this work never ends.”

References

- American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.) School-to-prison pipeline. www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/school-prison-pipeline.

- Centers for Disease Control. (2019, September 5). Racial and ethnic disparities continue in pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html.

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020, July 24). Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

- Duffy, M. & Duffy, D. (2002). Children of the universe. Santa Rosa, CA: Parent Child Press.

- Indigenous Corporate Training. (2017, March 29). A brief definition of decolonization and indigenization. www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-brief-definition-of-decolonization-and-indigenization.

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New York: Penguin Random House.

- Montessori, M. (1967). The discovery of the child. Notre Dame, IN: Fides.

- Schlosser, E. (1998, December). The prison-industrial complex. www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/12/the-prison-industrial-complex/304669.

- Tatum, B. D. (2017). Why are all the black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? And other conversations about race. New York: Basic Books.

About the Author

Interested in writing a guest post for our blog? Let us know!

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS.