Practical Life: Avoiding the Pinterest Pitfall (From the Summer 2022 Issue of Montessori Life Magazine)

This article was featured in our 2022 Summer edition of Montessori Life magazine. Read full issues online (AMS members only).

AMS members also receive a print subscription to Montessori Life magazine. Become a member today to receive your own subscription plus access to the complete digital archives.

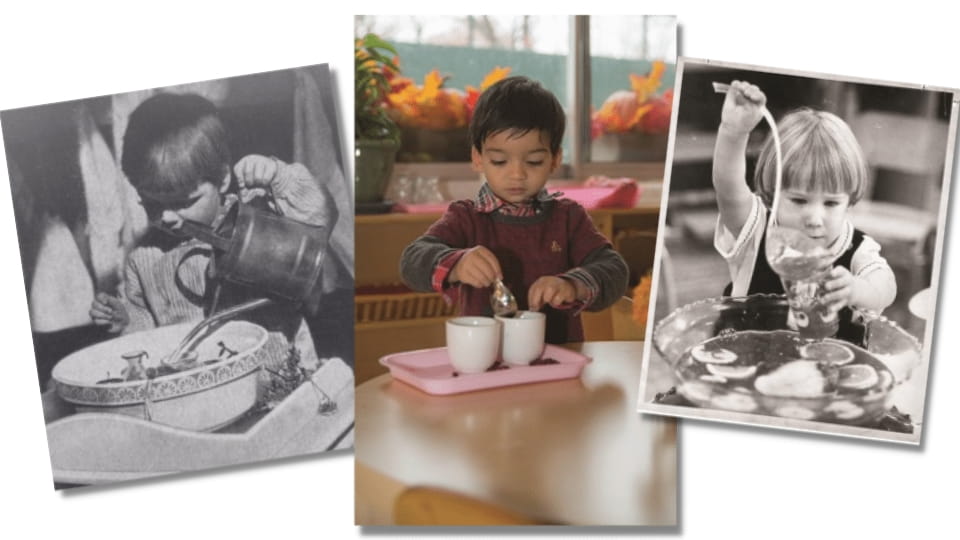

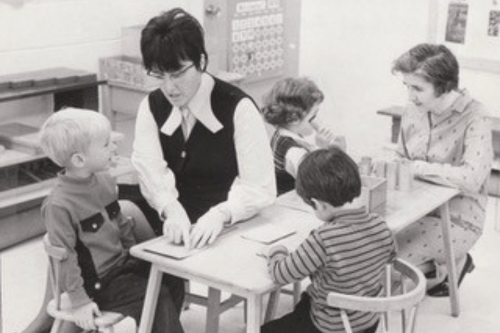

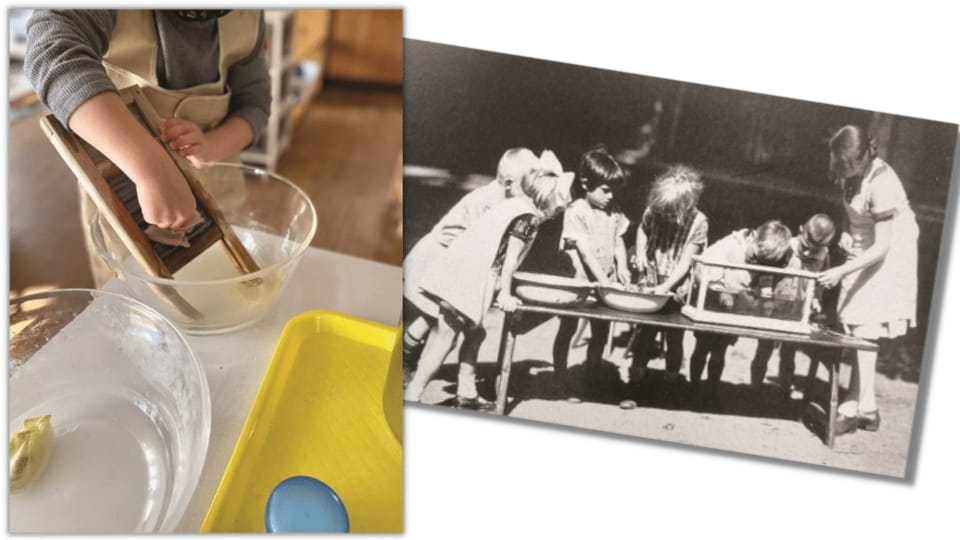

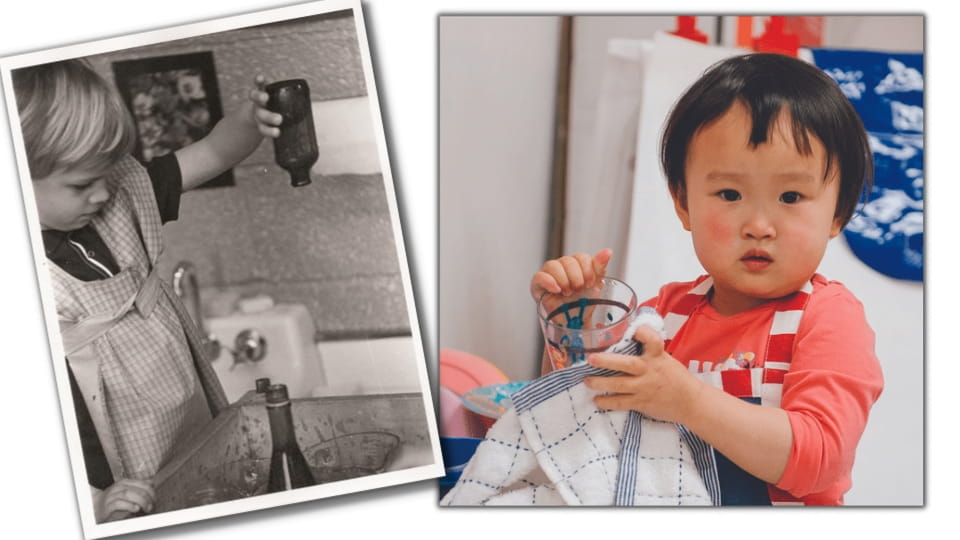

When Dr. Montessori began her work with young children in a working-class housing project in Italy, in 1907, her first prepared environment was not called a school but rather a “Children’s House.” And the first materials were not Sandpaper Letters or the Pink Tower but activities of Practical Life. Much of the Montessori Method that Early Childhood guides know and practice today is based on this early work (Pickering, 2012).

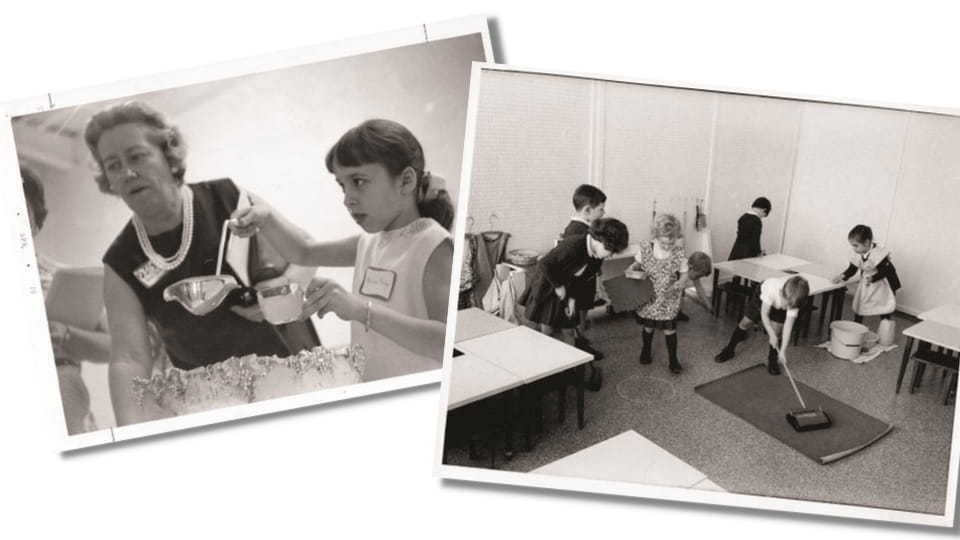

Many of today’s Montessori classrooms look much different from the early Children’s Houses of Dr. Montessori’s time. Montessori schools in the early 20th century functioned as an extension of the home, providing a safe space for the children of parents who worked long hours. Children in the earliest Montessori schools often spent 10 to 12 hours a day at school. This long, uninterrupted day was not only necessary for working parents but prescribed by Dr. Montessori. In her writing, she described an ideal day in the Children’s House, which would begin at 7 a.m. and wrap up by 6 p.m. American mothers and educators traveled to Europe to witness these environments firsthand and were struck by how well the children fared after such long days (Pickering, 2012).

These days included preparation and cleanup of more than one meal, along with plenty of time for uninterrupted work and social activity. Children were heavily involved in the processes of cooking and cleaning and were provided endless other opportunities for practical activities throughout the day:

[The children] put on the little aprons. The children are able to put these on themselves, or with the help of each other. Then we begin our visit about the schoolroom. We notice if all of the various materials are in order and if they are clean. The teacher shows the children how to clean out the little corners where dust has accumulated, and shows them how to use the various objects necessary in cleaning a room—dust cloths, dust brushes, little brooms, etc. All of this, when the children are allowed to do it by themselves, is very quickly accomplished. (Montessori, 1912, p. 131)

This early work with Practical Life gave Dr. Montessori some of her first insights into concentration and normalization (Pickering, 2012).

These days, while some Montessori programs worldwide and some public Montessori programs in the United States do provide longer extended days with more than one meal to accommodate working families, most children experience the Montessori classroom in a more abbreviated way. Some go to a morning or half day program that can be as short as 3 hours, while a “full day” is typically around 7 hours. When teachers must cram a day’s worth of activity into this 3- to 7-hour period, the work of preparation and tidying is often pushed to the time before and after school. The entire Montessori philosophy can end up restricted to one 3-hour work cycle, with children rushed to outside playtime, naptime, or specials in the remaining time.

In addition, today’s Montessori children often enter a classroom expected to begin a 3-hour work cycle with academically focused materials that directly support reading and math skills. This hearkens back to the roots of American Montessori education. In the early 1900s, Dr. Montessori was welcomed to the U.S. with open arms, revered for her rumored miracle children. Wealthy American parents were enchanted with this method of education that seemed to crank out high-achieving students. However, enthusiasm diminished when American educational philosophers like John Dewey and William Kilpatrick became uncomfortable with the uncentered role required of the Montessori teacher, and Montessori as a method of education fell out of favor in the U.S. By the 1950s and 1960s, Montessori schools in the U.S. were nearly extinct, until Nancy Rambusch and others resuscitated the American Montessori Movement. Fast-forward to the 21st century: today’s educational climate again prioritizes early academic achievement, which has helped create a resurgence in Montessori education among wealthy American families seeking alternatives to public schools. This growing popularity has led to a wider acceptance of Montessori education among modern policy-makers and educators (Whitescarver & Cossentino, 2008).

This strong focus on math and reading skills affects the delivery of Practical Life activities, which subsequently may be viewed (by parents, educators, and administrators) as simply “3-year-old work.” Standards in reading and math can pressure teachers to put Practical Life on the back burner. Modern Practical Life shelves can become limited to transferring lessons and crafts inspired by the current holiday season or Pinterest board, with limited space and time for activities like cleaning and preparing food.

A quick search of “Montessori activities” on Pinterest yields activities like putting colorful sponges in a tub of water, spooning dyed rice, and stringing seasonal bells on pipe cleaners. Even if “Practical Life” is specified in the search, these types of activities still flood the screen. And Pinterest is not the only online space that offers cutesy Practical Life ideas: DIY blogs, Montessori-inspired social media influencers, and trendy handmade materials on sites like Etsy are a sea of shelfie inspiration. As a result, “work” such as filling ice-cube trays, matching colored clothespins, and putting seasonally colored toothpicks into a cheese shaker fill Practical Life shelves both in homes and Early Childhood classrooms.

When Montessori must be done in as little as 3 hours, these activities can be inviting to adults who need to fill up a Practical Life shelf and still get to all those math and reading lessons. They are easy to put together, and they support fine-motor skills. They are colorful and often clever, something most people think is inviting to young children. They limit what could be timeconsuming messes that can come with inviting young children to cook and clean. And so many people, from your favorite Montessori influencer to classroom teachers on sites like Teachers Pay Teachers, are using them with what seems like success. However, do these types of activities meet the criteria for Practical Life?

Montessori saw the work of everyday life as the means for intelligent movement and found that movement without purpose is fatiguing to children. She believed that intelligent movement leads to concentration and normalization (Montessori, 1917). In the 1946 London lectures, Montessori said:

There is no limit to the amount of work there is to be done in the world. If you love working, there is a lot to choose from, and education must integrate this. We must understand that the exercises of practical life are not intended as training for the acquisition of practical skills. They are a kind of gymnastics training for the harmonious development of the psychic and motor parts of the individual. The individual becomes a unity so that a movement is not just a movement of the hand, but a movement of the whole person. (2012, p. 162)

Activities like baking bread, scrubbing the floor or a table, and arranging flowers all support the development of fine- and gross-motor skills while giving children the opportunity to feel like contributing members of their community, whether at home or in a classroom. “Children who act with purpose are happy because they are concentric with humanity’s vital function” (Montessori, 2012, p. 166). These types of practical tasks support the movement of a child’s whole person. Daily life’s messy, mundane practical activities are nonnegotiable for an authentic Montessori environment.

Dr. Montessori noted that imitating the work of adults was an important component of Practical Life activities. In the 1946 London lectures, she said: “It is interesting to notice that where life is simple and natural and where the children participate in the adult’s life, they are calm and happy” (Montessori, 2012, p. 152). The same joy and satisfaction from participating in everyday life activities cannot be replicated with a Pinterest-inspired activity or craft. According to a 2018 study by Taggart, Fukuda, and Lillard, children prefer real-life activities over their pretend counterparts. The research shows that children would rather cook in a real kitchen than pretend to cook in a play kitchen. They prefer cleaning with actual household tools to playing with toy versions. In this same study, children from Montessori classrooms demonstrated a greater preference for real life activities than their pretend counterparts.

While Pinterest-inspired activities are not strictly pretend play, do exercises like tonging with new “filler” objects for each season truly meet a child’s preference for real-life activities? There is evidence that fine-motor activities with practical tools like spoons and tongs benefit fine-motor development in young children (Rule & Stewart, 2002). According to Dr. Montessori, Practical Life aims to prepare children for the work of daily life and marry intelligence with movement. “The problem is not to move but to move in relationship with…intelligence…. We move a great deal in ordinary life, because muscular movement is intimately connected with the nervous system and is guided by the intelligence.” (Montessori, 2012, pp. 159, 164). The isolation of difficulty for practical skills happens by giving children one step activities that often involve the tools they will use in these real-life tasks. A child cannot wash the table or floor successfully without mastering skills like pouring and squeezing a sponge. Children cannot successfully bake bread without the fine-motor skill to spoon dry ingredients. In addition, the isolation of difficulty in Practical Life is essential for Practical Life work presented to children with learning differences and processing disorders (Pickering, 2004). Dr. Montessori tinkered with her approach and materials as she observed needs in development (Lillard & McHugh, 2019). How can Montessori educators provide these isolated activities without losing their souls to Pinterest?

Maria Montessori challenged adults to be thoughtful of the items placed within the environment (2012, p. 179):

We must not abandon the child to a haphazard choice of objects in the house or street. He will try to understand this world, and so we must give him a prepared environment with people who understand his needs—a beautiful, rich environment.

There is a place for isolated activities on trays in Practical Life, but we must also embrace those messy, daily practical tasks—even the ones that nearly always take longer with young children. In as few as 3 hours a day, Montessori guides can offer opportunities for meaningful Practical Life activities. Simple food preparation activities such as making lemon water can support the skill of pouring. Skip the colorful, Pinterest-inspired fine-motor activity and re-present those Dressing Frames that might be collecting dust. Preparing the environment is essential, but it should not be left up to the teacher. Instead of making sure the work rugs are neat first thing in the morning, let the children roll them for the day. Leave the towels unfolded for the children to fold, and keep the chairs on the tables for little hands to take down and push in. Children are eager to work. Let’s leave a little work for them to do.

References

Lillard, A. & McHugh, V. (2019). Authentic Montessori: The dottoressa’s view

at the end of her life, part 1: The environment. Journal of Montessori Research,

5(1). https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v5i1.7716

Montessori, M. (1917/1965). Spontaneous activity in education: The advanced Montessori method (F. Simmonds, Trans.). Schocken Books.

Montessori, M. (2012). The 1946 London lectures. Montessori-Pierson Publishing.

Pickering, J. (2004). Helping students with learning differences through the Practical Life curriculum. Montessori Life, 16(3), 20–21.

Pickering, J. (2012). The importance of uninterrupted time. Montessori Voices, 9–13.

Rule, A. & Stewart, R. (2002). Effects of Practical Life materials on kindergartners’ fine motor skills. Early Childhood Education Journal, 30(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016533729704

Taggart, J., Fukuda, E., & Lillard, A. (2018). Children’s preferences for real activities: Even stronger in the Montessori Children’s House. Journal of Montessori Research, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v4i2.7586

Whitescarver, K. & Cossentino, J. (2008). Montessori and the mainstream:

A century of reform on the margins. Teachers College Record, 110(12),

2571–2600. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811001202

About the Author

|

Margaret Beagle, MEd (she/her) is a Primary guide at Montessori Academy in Nashville, TN, where she lives with her husband and three children. She is AMS-credentialed (Early Childhood). Find her at www.wholechildcollaborative.com. |

Interested in writing a guest post for our blog? Let us know!

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS.