Promoting Cultural Fluency through Folktales in Elementary Classrooms

“But don't be satisfied with stories, how things have gone with others. Unfold your own myth.”

― Rūmī, Maulana Jalāl al-Dīn, and Coleman Barks. The Essential Rumi, Castle Books, New Jersey, 1997. (P 41)

Rose, a frail 10-year-old child, staggers across the endless expanse of the desert. Her mouth is parched, lips cracked like diminutive canyons. She swallowed, another failed attempt to quench her thirst with now non-existent saliva. The next step forward seemed dangerous. Too dangerous to expend energy from her body that has already burnt the last of its resources to keep her upright. Her dirt-crusted fingers scratched her hair and at that precise moment, she felt something cool on her hands. She looked up to see a darkened sky that seemed to have sprouted a million holes as rain drops slipped through them. Rose’s lips parted in a slow smile as a drop landed on her blood-crusted lips, obliterating the throbbing heat.

Now, take a deep breath and tune into your feelings. Where do you feel the story in your body? Dropped shoulders? A brief sigh? To me, this story always elicits a sense of tenderness towards Rose even though Rose is a fictional character I created just a few weeks ago. We refer to stories like these as “feel-good” stories. The term that has been used primarily based on the experiential effects is also, thanks to the burgeoning studies, scientifically accurate. Among many studies done on the effects of stories on people—almost all pointing to its positive effects—one study that involved 81 hospitalized children showed that children who listened to stories for 30 minutes every day showed a nine times increase in oxytocin, a prosocial hormone, and significant decrease in cortisol and pain scores.

Stories have shaped our behavior for over a millenia. They are powerful tools that create social cohesion, promote ethics, and strengthen the sense of togetherness in a community. In early civilizations, the narrative immersion experiences of stories were intended to lay down moral foundations even as they were used as a dependable form of entertainment. Stories educate, entertain, and connect people. Emotionally stimulating stories have also shown to build interpersonal empathy and social cognition.

Stories as Empathic Bridges

The power of stories lies in their ability to build a sense of belonging. They are the empathic bridge that connects us with characters—humans and non-humans alike. And stories do not just improve our relationship with others. They transform our relationship with ourselves. Stories tell us that inadequacies and challenges are part of the shared human experience and, as Kristin Neff, the renowned social psychologist on self-compassion, notes: it is that recognition that “we all go through something, rather than being something that happened to me alone” that opens the pathway for self-compassion.

And folktales, in particular, come with a valuable historical lens. They are brief, laden with numerous messages from the dangers of lying (The Boy who Cried Wolf); the importance of keeping a promise (Tsuru no Ongaeshi—The Japanese Crane story); to wisdom over brute strength (The Monkey and the Crocodile from Jataka tales).

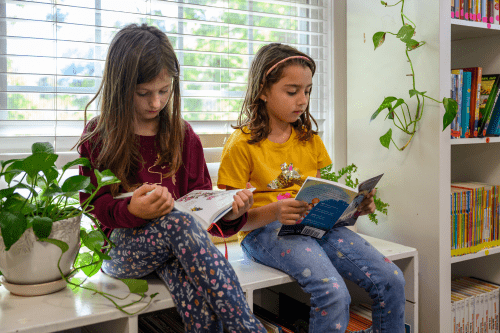

For children in the second plane of development, folktales offer an imaginative window into the cultural practices and moral values of a time in the past. The fluidity of folktales, given their evolutionary nature, make every retelling of a story as unique as its teller. In a classroom where folktales are routinely narrated, the students explore the vicissitudes of life through a multicultural lens. They learn about the Ghanaian story of Anansi, the spider who bargained away the rights, Indonesian mouse-deer Kantchil who tricked elephants, the fisherman of Japan whose opened a magic lacquer box that undid his wish for immortality, and a clever Indian judge who resolved a case between two traders.

Navigating Moral Compass through Stories

While the explicit morals of the folktales might seem too simplistic, the deeper wisdom embedded in the stories is accessible for those who look for it. In the story the Loyal Mongoose from Panchatantra Tales, the mongoose that saved the life of the baby by attacking a snake would be killed by the mother who would mistakenly infer that the mongoose had harmed her child. Alongside the explicit moral of the story “think before you act,” the story carries a plurality of deeper messages. The mother’s action could be seen as a paradigm for implicit bias, a term coined by Mahzarin Banaji that explains how our latent beliefs or past experiences influence our actions, or for the effects of social misinformation and our embedded psychological barriers to knowledge revision. The meaning and messaging of any folktale could be created by the guide and students together through parsing the finer elements of the story.

Discussions and follow-up activities including compare and contrast of folktale variations help students see a society as an entity that is complex and constantly changing and growing. It paves a way for creating a Holistic Indigenous Learning model, as proposed by Dr. Ulcca Joshi Hansen in her book The Future of Smart: How Our Education System Needs to Change to Help All Young People Thrive, wherein “[students] are encouraged to be self-reflective and aware of how contingent and changeable their perceptions are.”

Folklore Variations

Folktales, by virtue of branching out and taking root in different parts of the world, often appear with acculturated variations. According to a 2012 study, there are 333 variations of Little Red Riding Hood recorded in European nations, not including the possible variations of the stories in Asian and African traditions. It is crucial for educators to highlight and analyze with the students the cross-cultural relationships among folktales. During one of my social studies classes with 5th graders, we analyzed Cinderella variations that led to a Socratic discussion on the societal framework during different times. The students critically examined the variations as they discussed why Western variations have a fairy godmother while the Egyptian story has a kind master and an Eagle god who transforms the fate of Cinderella (or in this case, Rhodopis) for the better. The discussion provided a segue into global slave trade before the European conquest, cross-cultural perception of beauty, and the Black experience in Ancient Egypt.

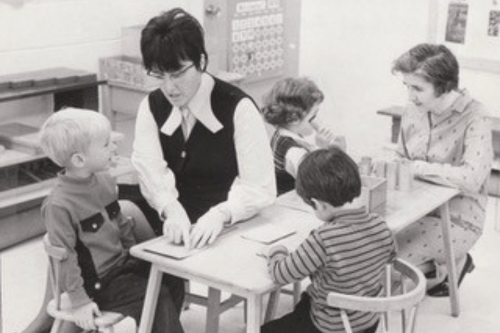

Maria Montessori calls storytelling “a cosmic task.” She envisioned Cosmic Education to be a catalyst for children to widen their horizons through cultural stories. To effectively incorporate folktales into the classroom, Montessori educators must sieve through stories that are age-appropriate and culturally authentic. A follow-up discussion after the read-aloud is critical to provide context for the stories and encourage students to make connections between the themes and events in the tale and the evolving moral landscapes.

Here are some guidelines for incorporating folktales in your classrooms:

- Choose age-appropriate stories: Make sure the stories you select are appropriate for the age and maturity level of your students. You can also choose stories that align with the subject matter you are teaching.

- Provide context: To help students fully appreciate the cultural and historical significance of the stories, it's important to provide some context for the tales. This might involve discussing the cultural traditions from which the story originates or providing some historical background on the period in which the story was created.

- Encourage critical thinking: You can encourage students to analyze the characters, plot, and themes of the story and consider how these elements relate to the social and cultural context in which the story was created.

- Promote empathy and understanding: By exploring stories from different cultures and traditions, students can gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human experience and develop greater empathy for people who may be different from themselves.

- Incorporate creative activities: Always find ways to add kinesthetic elements to the activity. For example, you might ask students to create their own versions of the story, create a tableaux, act out a scene from the story, or create a group play.

Stories are one of the most transcendent forms of human connection. And by constructing a culture of analyzing folktales in the classroom, we are not only offering an imaginative ladder for students to step onto as they make sense of the world, we are also teaching them to step out of the black-and-white moral landscape and navigate gray spaces with curiosity.

References

How Could Children’s Storybooks Promote Empathy?

Study on Psychological Drivers of Misinformation Belief

Hansen, Ulcca Joshi. The Future of Smart: How Our Education System Needs to Change to Help All Young People Thrive, Ulcca Hansen Consulting LLC, La Vergne, 2021, pp. 103–103.

Duffy, Michael and D'Neil. Children of the Universe: Cosmic Education in the Montessori Elementary Classroom, Parent Child Press, Hollidaysburg, PA 2002, pp. 5-6.

About the Author

|

Aishwarya Saminathan is an Upper Elementary teacher at Princeton Montessori School, where she has successfully integrated folktale study into her social studies curriculum, recognizing its power to inspire and engage students. Prior to her teaching career, Aishwarya worked as a senior reporter in India, writing extensively about school education in rural areas. Mother of two girls, she enjoys long walks and library hopping with her kids. AMS-credentialed (Elementary I and II). Contact her at asami@princetonmontessori.org. |

Interested in writing a guest post for our blog? Let us know!

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS.